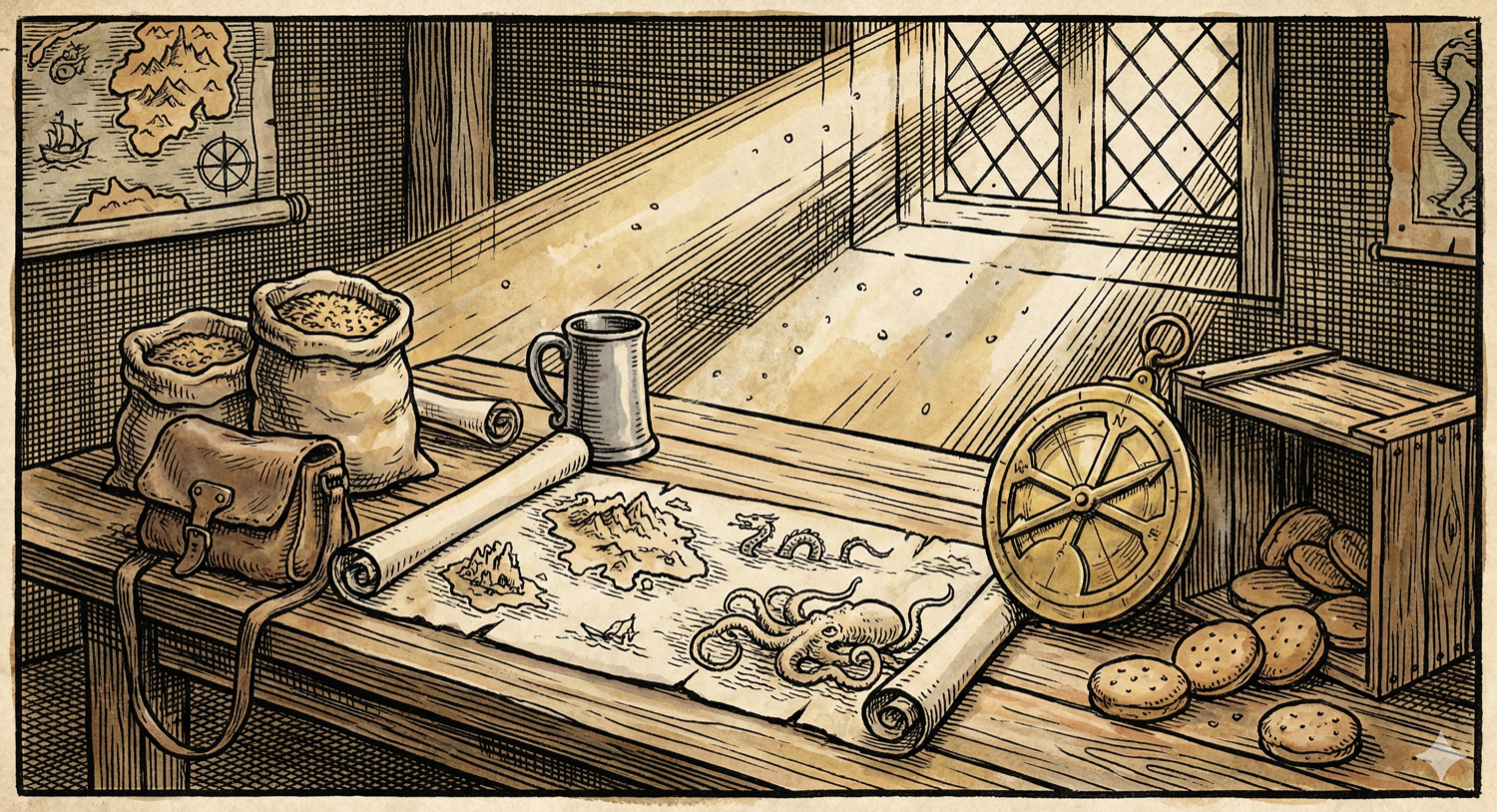

Understanding The Waters - Adhd Autism Pda And Odd Explained

Free Chapter

Quick Map: If you only read one page, read this

- The Ferrari Engine (ADHD): Not a deficit of attention, but a dysregulation of it. High stimulation is the fuel; the "Navigation Desk" (Executive Function) is the underdeveloped braking system.

- The Different OS (Autism): Not broken, just running Linux in a Windows world. Hyper-connectivity in local neural networks creates "Sensory Cliffs" where everyday inputs can become deafening roars.

- The Autonomy Drive (PDA): For some children, demands feel like life-threatening dangers. Control is their safety mechanism; "Low-Demand" navigation is the key to preventing panic.

- The Protective Shield (ODD): A "threat-biased" neuroception misreads safety as danger. Defiance is a preemptive strike from a soldier stuck behind enemy lines, not a behavior problem.

- The Tangled Map (Comorbidity): These conditions rarely sail alone. Strategies for one (routine) may trigger another (PDA). Success means mapping the specific intersections of your child's brain.

Neurodevelopmental Conditions 101: A Cartographer's Guide to Open Waters

The first step in any voyage is studying the chart. In neurodivergent parenting, however, the chart we are handed often bears little resemblance to reality. We receive clinical labels—lists of deficits and deviations. These read like an autopsy of behavior rather than a guide to a living child.

We are told what is "broken," but rarely how the machine actually works. To survive, we must become cartographers of a new kind. We must learn to distinguish a reef of sensory overload from a slack tide of dopamine deficiency.

In this seascape, misreading conditions is a hazard. Treating an autistic meltdown like a defiant tantrum is like pouring water on a grease fire. The resulting explosion is inevitable. We cannot navigate what we do not understand. This chapter is a cartography of the four primary currents: ADHD, Autism, PDA, and ODD.

We fuse narrative with neurobiology. We look at the "why" beneath the "what." We aren't searching for parts to fix; we're searching for the missing operating manual. By understanding these conditions—the racecar velocity of ADHD, the Linux system of Autism, the autonomy drive of PDA, and the shield of ODD—we move from combat to collaboration.¹

The Philosophy of the Map: Biodiversity of the Mind

Before we chart the first current, we must calibrate our compasses. The medical model views these conditions as pathology. It defines every deviation as a deficit. It lists things the child cannot do.

The neurodiversity paradigm offers a different view. It posits that these neurological variations are natural forms of human biodiversity.² A robust ecosystem requires the oak, the willow, and the wildflower. Human society requires both linear and divergent thinkers.

Our children have specialized brains, not broken ones. They are race cars in a school zone. Understanding this is the difference between fighting your child’s nature and harnessing it.¹

---

Current 1: ADHD – The Racecar Brain with Bicycle Brakes

The Metaphor: Velocity Without Viscosity

ADHD is a confusing name. It suggests a "deficit" of attention. But any parent who has watched her child build Lego for six hours knows that is wrong. ... To parent an autistic child, we must stop trying to make her "PC compatible." We must learn to code in her language. ADHD is not a deficit of attention; it is a dysregulation of it. It is an abundance of attention, uncontrollable and flooding the system. It is like a fire hose without a valve.

Dr. Edward Hallowell describes this as having a "Ferrari engine with bicycle brakes".³ The engine is the child's intellect and creativity. It moves at a velocity that leaves others breathless. The brakes are the inhibitory systems—the ability to slow down, stop, and reflect.⁸

Imagine a child named Maya. Maya darts through life like a rocket. She has a mind that moves at the speed of light. She makes connections that others miss. But Maya also forgets her backpack every morning. She interrupts conversations because thoughts burn a hole in her tongue. She isn't being rude; her engine is revving at 5,000 RPMs, and her brakes are made of bicycle pads. They simply cannot hold the machine.⁴

The Neuroscience of the Engine: The Dopamine Drought

To understand why Maya cannot just "sit still and listen," we must look at the molecular fuel of the brain: dopamine. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter responsible for reward, motivation, and the feeling of satisfaction. It is the chemical signal that says, "This is important, pay attention," or "Good job, keep going." In the neurotypical brain, dopamine flows reliably, maintaining a baseline of interest and alertness that allows a child to endure the mundane—a boring math class, a long dinner, a repetitive chore.⁵

Research using PET and SPECT imaging suggests that some individuals with ADHD show differences in their dopamine pathways.⁷ Some studies report higher dopamine transporter (DAT) availability in the striatum.¹ These transporters act like over-eager vacuum cleaners, sucking dopamine back into the neuron before it has a chance to bind to the receptor and transmit the "satisfaction" signal.

Some researchers describe this pattern as a form of reward deficiency, though terminology and findings vary. While the neurotypical brain has a full tank of gas, the ADHD brain can feel like it is running on fumes. This biological reality drives behavior. When an ADHD child jumps off the couch, pokes her sibling, or interrupts you, she is not trying to be annoying; she is often unconsciously self-medicating. She is engaging in high-stimulation behaviors to trigger dopamine, attempting to bring her brain up to the baseline alertness that others take for granted.¹ The hyperactivity is not "bad behavior"; it is the engine revving to keep from stalling.

The Interest-Based Nervous System

This dopamine dynamic explains the confusing paradox of ADHD: "Why can she focus on video games for hours but can't do five minutes of homework?" The answer lies in the nature of the nervous system. A neurotypical brain has an Importance-Based Nervous System; it can prioritize tasks based on external importance (e.g., "I must do this because the teacher said so"). The ADHD brain has an Interest-Based Nervous System. It does not respond to importance; it responds to stimulation.

- Interest: Is it fascinating?

- Challenge: Is it difficult or competitive?

- Novelty: Is it new or different?

- Urgency: Is the deadline right now?

If a task meets these criteria, the ADHD brain floods with dopamine, leading to hyperfocus—a state of intense, unbreakable concentration.⁹ If the task lacks these elements (like routine homework), the dopamine taps run dry, and the brain literally shuts down. It is not that the child won't focus; it is that she biologically can't engage the starter motor without the fuel of interest.

The Neuroscience of the Brakes: The Navigation Desk Down

The "brakes" of the brain reside in the prefrontal cortex and the frontal lobes. This is the headquarters of Executive Function, the cognitive system often compared to a Chief Navigator.¹ This navigator is responsible for managing the flow of information and behavior. In the ADHD brain, this Navigation Desk matures more slowly—often three to five years behind peers in development.⁹

The Navigation Desk manages four critical tasks, each of which is often compromised in ADHD:

- Inhibition (The Brakes): The ability to stop an action or impulse. A child with poor inhibition speaks before thinking, grabs the toy before asking, or hits when angry. The gap between stimulus and response is nonexistent.

- Working Memory (The Navigation Chart): The ability to hold information in the mind while using it. This is the brain's "RAM." When you tell a child, "Go upstairs, put on your socks, and bring down your laundry," you are uploading three files to their working memory. In an ADHD brain, the working memory capacity is often smaller or "glitchy." By the time she reaches the stairs, "laundry" has been deleted. By the time she enters the room, "socks" has been overwritten by "Oh look, Lego!" This is not defiance; it is a data storage failure.¹⁰

- Emotional Regulation (Turbulence Control): The ability to manage frustration and reaction. Because the inhibitory "brakes" are weak, emotions can surge quickly and stay elevated. Disappointment isn't just a bummer; it's a tragedy. Excitement isn't just happiness; it's mania. Research on ADHD documents clinically significant emotion dysregulation and heightened reactivity.¹¹ Some families describe intense rejection sensitivity, sometimes called Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD), but the core issue is emotion regulation.

- Time Horizon (The Radar): The ability to see the future consequences of current actions. The ADHD brain is often described as having "time blindness." It lives in two time zones: "Now" and "Not Now." If a deadline is not in the "Now," it does not exist emotionally. This makes working toward future rewards excruciatingly difficult.

When you ask an ADHD child to perform a multi-step routine, you are asking their understaffed navigator to land three vessels simultaneously while the radar is blinking on and off. If the navigator fails, the child will inevitably end up playing with Lego in her underwear, having forgotten the socks entirely. This is not a moral failing; it is a neurological system failure.¹

Field Guide: ADHD Fact Sheet

| Category | Data Points & Insights |

|---|---|

| Prevalence | Approximately 5-10% of children worldwide are diagnosed with ADHD, though rates vary by diagnostic criteria.¹³ |

| Heritability | ADHD is highly genetic, with heritability rates estimated between 74% and 88%.14 It is roughly as heritable as height. If a child has it, there is a statistically high probability one or both parents have it (diagnosed or not). |

| Comorbidity | ADHD rarely travels alone. 50-60% of children with ADHD also meet criteria for Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) 16, and overlap with Autism is estimated at 30-80% (AuDHD).¹ Anxiety and depression are also common passengers.¹³ |

| Key Insight | Inattention is a myth. It is actually distractibility, a byproduct of high curiosity. The ADHD brain is a wide-angle lens in a world designed for telephoto focus. It processes everything—the hum of the fridge, the bird outside, the tag on the shirt. |

Reframing the Traits: The Superpowers of the Racecar

We must move away from the language of "symptoms" and toward the language of "traits." Every deficit in the ADHD brain has a corresponding strength:

- Impulsivity is the flip side of decisiveness and courage. It is the ability to act without overthinking, which can be a superpower in emergencies or entrepreneurial ventures.

- Hyperactivity is energy and endurance. It is the fuel for athletics, performance, or tireless work ethic.

- Distractibility is creativity and observation. It is the ability to notice what others miss and to make lateral connections between seemingly unrelated ideas.

Our job as co-parents is not to dismantle the racecar, but to help the driver install better brakes so they can steer that incredible machine where they want to go.

---

Current 2: Autism Spectrum – The Different Operating System

The Metaphor: Windows vs. Linux

If the neurotypical brain runs Windows—a standard, compatible system—the Autistic brain runs Linux. Linux is specialized and powerful. It is capable of feats that Windows cannot touch—unrivaled stability and processing for specific tasks. However, it requires different inputs and drivers. Social software often fails to run without an emulator.¹

For decades, the world has tried to force Windows updates onto Linux brains. This results in crashes and overheating. To parent an autistic child, we must stop trying to make them "PC compatible." We must learn to code in their language.

The Science: Hyper-Connectivity and the Sensory Cliff

Current neuroscience suggests unique connectivity patterns in the autistic brain. There is often hyper-connectivity in local neural networks and hypo-connectivity in long-range networks.¹⁷

- Local Hyper-connectivity: This explains the ability to focus on details and specific interests. This is called Monotropism—an attention strategy where the brain devotes massive resources to a single task. Interrupting this focus is physically painful. It creates "cognitive whiplash" that can trigger a meltdown.

- Long-range Hypo-connectivity: This makes it harder to integrate complex information quickly. Social interaction requires processing faces, tone, and body language simultaneously. For an autistic brain, this information arrives in fragmented packets. It takes immense effort to assemble a coherent picture.

This wiring leads to "Sensory Cliffs." The autistic brain often lacks the filters that neurotypical brains use to dampen noise. To you, a fridge hum fades away. To an autistic child, it might be a roar that never stops. A tag on a shirt can feel like a razor blade.¹ This is a physiological reality. Some studies suggest heightened threat reactivity and differences in amygdala development that may contribute to chronic arousal.¹⁸

The Narrative: A Day in the Life

Imagine you are attending a cocktail party. But in this party, the lights are strobing like a disco, the music is playing at maximum volume, and the floor is covered in sandpaper. The smell of the hors d'oeuvres makes you nauseous. Everyone is speaking a language you only partially understand—they use idioms and sarcasm that make no logical sense—and they get angry when you don't respond instantly or when you cover your ears.

This is the daily reality for many autistic children in a standard classroom or supermarket. When she meltdowns, it is not a "tantrum" to get a toy; it is a system crash caused by sensory and cognitive overload. The screaming or shutting down is her brain's emergency reboot sequence.

The Four Faces of Autism: Why "The Spectrum" is Actually Multiple Spectrums

You may have noticed that two children with the same "autism" diagnosis can look completely different. One child is non-speaking with severe cognitive delays. Another is verbally fluent, socially awkward, and academically advanced. Both are autistic—but their daily realities are worlds apart.

Emerging genetic research suggests a possible explanation: Autism may not be one linear spectrum, but rather multiple biologically distinct subtypes.

Preliminary research analyzing large genetic cohorts (including the SPARK study) has identified evidence for four distinct clusters within the autism spectrum, each potentially associated with different genetic programs and developmental trajectories. While this framework is still being validated by the research community and not yet widely adopted in clinical practice, it offers a useful lens for understanding why your child's autism may look nothing like your neighbor's—and why strategies that work for one autistic child may fail catastrophically for another.

Important Caveat: The subtype framework presented below represents emerging genetic research that is not yet peer-reviewed or clinically standardized. These categories are based on preliminary data and should be viewed as a conceptual tool for understanding heterogeneity, not as diagnostic categories. However, the framework validates what many families already know: autism presents very differently across individuals, and these differences likely have biological roots.

Table 2.1: The Four Genetic Subtypes of Autism

| Subtype | Presentation | Genetic Pattern | What This Means for Co-Parenting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | Intense social rigidity, repetitive behaviors, restricted interests. Often average or above-average IQ. | Linked to polygenic risk scores for cognitive rigidity and synaptic function. Strong familial transmission. | Parents may see "stubbornness" or "refusal," but the root is genetic predisposition to rigidity. Interventions should prioritize flexibility skills over rote compliance. This child may be exhausted from masking at school. |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | Core autistic traits PLUS global developmental delays in motor and language skills. | High burden of de novo (spontaneous) mutations and rare variants. Often distinct from parents' genetic profile. | Parents may not "see themselves" in this child as clearly because the genetic cause is likely spontaneous, not inherited. This child requires robust wraparound support and is most likely to have co-occurring medical issues. |

| Moderate Challenges | Milder presentation of core traits; high camouflaging potential. Often termed "high functioning" (though this label is falling out of favor). | Strong familial transmission via common polygenic variants. High overlap with Broad Autism Phenotype (BAP) in parents. | The "Similarity-Fit" hypothesis is most relevant here—parents likely share these traits. Risk of late diagnosis is highest. This is the subtype where undiagnosed parents often recognize themselves. This child may appear "fine" but is burning out internally from masking. |

| Broadly Affected | High intensity across ALL domains: social, communication, motor, cognitive. Most visible support needs. | Complex combination of high polygenic load (common variants) PLUS rare, high-impact mutations. | Requires the most robust support systems. High likelihood of co-occurring medical comorbidities (epilepsy, GI issues). Parents may feel overwhelmed; external support (respite, therapy teams) is not optional. |

Why This Matters:

- Your parenting strategies must match your child's subtype. A "Moderate Challenges" child thrives on low-key accommodations and self-advocacy skills. A "Broadly Affected" child needs intensive environmental modification and communication supports.

- If you're an undiagnosed autistic parent, you likely match the "Moderate Challenges" profile. The genetic variants are strongly familial in this subtype. If your child is in the "Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay" subtype, their presentation may be driven by spontaneous mutations—not your inherited traits.

- "High functioning" vs. "low functioning" labels are misleading. A child in the "Moderate Challenges" subtype may appear more capable but is at HIGHER risk for autistic burnout due to masking demands. Support needs are not linear.

The takeaway: Two autistic children can have fundamentally different biological realities. The genetic programs driving their traits are distinct. This is not "mild vs. severe" autism—it is categorically different types of autism that happen to share some overlapping features.

If you find yourself thinking, "My child's autism looks nothing like the books describe," this is why. The books often describe only one subtype. Your child deserves strategies tailored to their specific genetic and phenotypic profile.

---

Special Profile: Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) – The Anxiety Drive

PDA is a distinct profile within the autism spectrum. It is often called a "Pervasive Drive for Autonomy".1

PDA is critical for co-parents to understand. Standard strategies—like rigid routines and direct instructions—often act as kryptonite. What calms a classic autistic child will send a PDA child into a panic.

The Mechanism: Autonomy as Survival

For a PDA child, a demand can feel like an intense threat. When you say, "Put on your shoes," her brain may register danger, as if being cornered by a predator. Control becomes her safety mechanism. This can trigger a lightning-fast fight-flight-freeze response.³²

This drive is so fierce that the child will resist things she wants to do (like eating ice cream) if she feels someone else is controlling her. This distinguishes PDA from ODD: the resistance is often irrational and harms the child's own interests.

The Vagus Nerve Connection

Using a model from Polyvagal Theory (a therapeutic framework for understanding stress responses), the PDA child may drop out of "Social Engagement" into "Mobilization" (fight/flight). If the demand persists, she may drop into "Immobilization" (shutdown). She might appear shut down or unresponsive.²³

The Mask: Social Lubrication

PDA children often use "social lubrication" first. They may use distraction ("Look at that bird!"), charm, or role-play. A PDA child might say, "I can't put on shoes, I'm a cat." She is trying to negotiate safety without conflict. When these fail, panic and meltdown ensue.

Field Guide: PDA Fact Sheet

| Feature | PDA Profile Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Core Drive | Anxiety-driven need for control and autonomy to feel safe.²⁵ |

| Avoidance Tactics | Distraction, negotiation, role-play, physical incapacitation ("my legs don't work"), withdrawing into fantasy.²² |

| Key Difference | Standard Autism: Thrives on routine and rule-following. PDA Autism: Resists routine if it feels imposed; thrives on novelty and flexibility.³² |

| IEP/Educational Planning | Critical: PDA is not a separate DSM-5-TR diagnosis. For IEP purposes, use "Autism Spectrum Disorder" as the primary disability category, then describe the demand-avoidant profile in the functional performance section. Schools cannot deny services because they don't recognize "PDA" as a standalone category. |

| Strategies | Low-Demand Parenting: Phrase demands as invitations or observations ("The shoes are by the door" vs. "Put on your shoes"). Use collaborative language ("I wonder how we can get ready on time?").²⁶ |

---

Current 3: Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) – The Rebel with a Cause

The Metaphor: The Soldier Behind Enemy Lines

ODD is a loaded term. It suggests a child who is willfully difficult. We must reframe this: ODD is a disorder of emotional dysregulation and threat detection.¹⁶

Imagine a soldier stuck behind enemy lines. This child scans the horizon for hostility. They wear heavy armor and carry a shield. They trust no one. Their brain tells them that everyone is out to control or shame them.

The tragedy is that the "armor"—the arguing and refusal—is mistaken for the child's personality. We see a "bad kid" who wants to fight. But beneath the shield is a terrified kid fighting for their life.¹

The Science: Threat-Biased Neuroception

Children with ODD often have threat-biased neuroception. Their subconscious system for detecting safety is more likely to register danger.²⁸

- The Neutral Face: Research shows these children often misread neutral faces as "angry" or "threatening."1

- The Protective Shield: Defiance is a preemptive strike. If the brain screams, "You are not safe," the biological response is to fight back. "You can't make me!" is a declaration of survival, not disrespect.²⁷

Neuroimaging reveals abnormalities in the amygdala and other emotional centers. These children often have deficits in "Hot Executive Functions." They can't think clearly when emotions are high. Unlike ADHD children who struggle with planning, ODD children struggle when the temperature rises.¹

Reframing the Traits: Defenders of Justice

Hidden in the ODD profile are strengths. These children are "Defenders of Justice".28 They have a profound sensitivity to fairness. They challenge authority that seems unjust or illogical. They are resilient and persistent.

The stubbornness of a 7-year-old is the grit of a future whistleblower or innovator. Our goal isn't to break their will. It is to help them lower their shields so they can connect.²⁷

---

Current 4: The Tangled Map – Comorbidity

Rarely do these currents stand alone. Your child’s map likely includes intersecting micro-climates. This is where standard advice fails most. Strategies for one condition may trigger another.

The AuDHD Paradox (Autism + ADHD)

Overlap between Autism and ADHD is massive (30-80%).³¹ Parenting "AuDHD" is like managing a civil war.

- The Conflict: The Autistic side craves order. The ADHD side craves novelty and chaos.³⁰

- The Result: The child begs for routine but rebels against it three days later. They organize toys meticulously but leave a mess elsewhere. They need connection but are quickly exhausted by it.

- Parenting Shift: You need "Structured Flexibility." Use routines with built-in variety. (e.g., "Pizza Night, but we rotate the toppings").

The ADHD + ODD Loop

Impulsivity feeds reactivity.

- The Mechanism: The ADHD brain acts without thinking. The parent corrects them ("Be careful!"). The ODD brain perceives this as an attack, triggering a meltdown. The child explodes because shame triggered their threat system.

- The Strategy: Treat ADHD impulsivity first. Use "Connect before Correct" to bypass the threat detection system.

The PDA + ADHD Accelerator

Strategies that work for ADHD, like Reward Charts, often backfire with PDA.

- Why it fails: For many PDA profiles, a chart feels like external control and can increase anxiety or avoidance, even when the child wants the reward.³²

- The Strategy: Use "Strewing." Leave interesting items out without comment. The ADHD brain is drawn to the novelty. The PDA brain engages because they discovered it.

---

Interactive Parent Toolkit: Mapping Your Child's Terrain

It is time to take out your pencils. We are going to draw the specific map of your child. This section includes exercises to help you move from theory to practice. As co-parents, doing this together can be eye-opening; you may find you are navigating two different versions of the same child.

Exercise 1: The Sensory Profile Map

Neurodivergent children often have "spiky" sensory profiles—seeking intensity in some areas while avoiding it in others. Knowing these spikes can prevent meltdowns.

Instructions: For each sense, mark where your child falls on the spectrum from "Avoider" (hypersensitive) to "Seeker" (hyposensitive). Discuss with your co-parent to see if behaviors differ between households.

| Sense | Avoider (Triggers) | Seeker (Glimmers/Anchors) | My Child's Profile (Notes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory | Covers ears, hates vacuums/crowds, startled by sudden noises. | Hums, loves loud music, speaks loudly, makes noise to focus. | |

| Visual | Hates bright lights, avoids eye contact, overwhelmed by clutter. | Loves spinning objects, flashing toys, screens, visual patterns. | |

| Tactile | Hates tags, socks, sticky food, light touch (tickling). | Loves deep pressure, hugs, fidgets, messy play (mud/slime). | |

| Vestibular (Movement) | Scared of swings, car sick, prefers sedentary play. | Spins, jumps, hangs upside down, constantly moving. | |

| Oral | Picky eater, hates textures/mixing foods. | Chews on shirts/pencils, loves crunchy/spicy/sour foods. | |

| Proprioception (Body Position) | Low muscle tone, clumsy, avoids sports. | Crashes into things, stomps, loves heavy blankets, roughhousing. |

Co-Parent Reflection:

- Observation: "I notice she seeks deep pressure (hugs) before bed at my house."

- Discrepancy: "At Dad's house, she seems to avoid loud noises more. Is the TV louder there?"

- Action Plan: "We will both incorporate a 'squeeze session' or weighted blanket time before bed."

Exercise 2: The "Dopamine Menu" (For ADHD/AuDHD)

Instead of nagging the child to "find something to do" (which is a demand), create a menu of activities that provide the dopamine hit their brain craves. This teaches self-regulation.

Create a visible menu (whiteboard/poster) with the child. Divide into:

- Appetizers (Quick hits): 5 jumping jacks, petting the dog, a sour candy, a fidget toy, drinking ice water.

- Main Courses (Deep focus): Lego building, drawing, coding, reading graphic novels, playing an instrument.

- Sides (Sensory help): Noise-cancelling headphones, weighted blanket, chewing gum, sitting on a yoga ball.

- Desserts (High reward/High cost): Screen time, video games (use sparingly or as a scheduled treat, as these can deplete dopamine receptors long-term and make "Main Courses" seem boring).

Exercise 3: The "Neuroception Safety Checklist" (For ODD/PDA)

When your child is defiant, before you correct the behavior, check the environment for hidden threats that might be triggering their neuroception.

Before correcting behavior, ask yourself:

- Tone of Voice: Am I speaking with a flat, low, calm tone (Safety)? Or is my voice spiked with frustration/sarcasm (Threat)? (ODD brains detect frustration as aggression).

- Face: Is my face relaxed? Or are my brows furrowed and jaw clenched?

- Posture: Am I towering over them? (Threat). Can I get below their eye level or sit down? (Safety).

- Phrasing: Did I issue a command ("Do this now")? Can I rephrase as a collaboration ("I bet we can beat the timer") or an observation ("I see the shoes are still on the floor")?

- Timing: Is the child currently dysregulated (red zone)? If so, no correction will be heard. Wait for regulation (green zone).

Parent Toolkit: The Neurotype Navigator

Goal: Map your child's specific neurotype profile by tracking observed behaviors, helping you identify which strategies to prioritize.

When to use: When you're newly diagnosed (or seeking diagnosis), when behaviors are confusing and contradictory, or when co-parents disagree about "what's wrong."

Time needed: 10-15 minutes to complete initial mapping, then ongoing observation over 1-2 weeks.

Materials: Paper or digital doc, this chart, your observations from daily life.

Steps:

Observe without judgment for 3-5 days. Watch your child in different contexts: morning routine, homework, transitions, social situations, sensory environments. Take notes on what triggers distress and what brings flow.

Check the boxes below for traits you observe consistently (not just once, but as a pattern):

ADHD Traits:

- Difficulty sustaining attention on "boring" tasks (homework, chores)

- Hyperfocus on high-interest activities (video games, Lego) for hours

- Forgets instructions mid-task (starts task, gets distracted, never finishes)

- Impulsive actions (interrupts, grabs, blurts answers)

- Constant movement (fidgeting, pacing, climbing)

- Time blindness ("5 minutes" feels like "now" or "forever")

- Emotional intensity (big feelings, fast escalation)

Autism Traits:

- Prefers predictable routines; distressed by unexpected changes

- Intense focus on specific interests ("special interests")

- Sensory sensitivities (sound, light, textures, smells)

- Difficulty reading social cues (tone, facial expressions, sarcasm)

- Literal interpretation of language ("It's raining cats and dogs" → looks for animals)

- Need for sameness (same food, same route, same order)

- Stimming behaviors (hand-flapping, rocking, repeating phrases)

PDA Traits:

- Extreme anxiety triggered by ordinary requests ("Put on shoes" → panic)

- Uses social strategies to avoid demands (negotiation, distraction, role-play)

- "Can't" vs. "Won't" (literally feels unable to comply, not defiant)

- Comfortable with demands they initiate or control

- Masking demands makes compliance easier ("I wonder if..." vs. "Do this")

- Meltdowns escalate when demands increase

- Need for autonomy feels like life-or-death

ODD Traits:

- Argues with adults frequently, especially authority figures

- Refuses to comply with rules, even reasonable ones

- Deliberately annoys or provokes others

- Blames others for mistakes or misbehavior

- Easily annoyed or angered by others

- Acts spiteful or vindictive

- Defiance is worse with one parent or in specific contexts (school vs. home)

Count your checks in each category. Most neurodivergent children will have traits in multiple categories (comorbidity is the norm, not the exception).

Map the intersections. Draw a simple Venn diagram with overlapping circles for each neurotype your child shows traits in. This is your child's unique profile.

Prioritize strategies. Based on your map:

- If ADHD is dominant → Focus on dopamine bridges, visual schedules, external working memory aids

- If Autism is dominant → Focus on predictability, sensory accommodations, literal/clear language

- If PDA is dominant → Focus on low-demand language, autonomy, collaborative problem-solving

- If ODD is dominant → Focus on connection, fairness, "sideways parenting," relationship repair

Test and refine. Try strategies for 2 weeks. If behaviors improve, you've found a match. If not, revisit your map—you may have missed a hidden trait.

Example Filled-In:

Parent: Sarah (Mom of 7-year-old Chloe)

Chloe's checked traits:

- ADHD: 6/7 boxes checked (hyperfocus, forgets mid-task, impulsive, emotional intensity, time blindness, movement)

- Autism: 2/7 boxes checked (sensory sensitivities to sound/textures, stimming when stressed)

- PDA: 1/7 boxes checked (sometimes uses negotiation to delay)

- ODD: 5/7 boxes checked (argues, refuses rules, blames others, easily annoyed, defiance worse with Dad)

Sarah's interpretation: "Chloe's profile is ADHD + ODD with some sensory sensitivities. The ODD behaviors might actually be ADHD impulsivity + weak emotional regulation, not true oppositionality. I need to focus on dopamine strategies (movement breaks, gamification) and relationship repair (connection before correction). The defiance with Dad might be because he uses harsh tone (triggers her threat response). We need to align on calm, predictable communication."

Priority strategies:

- ADHD: Visual timers, movement breaks, praise for effort (not just results)

- ODD: Repair rituals after conflicts, validate feelings before correcting behavior

- Sensory: Noise-canceling headphones for homework, tagless clothing

IF CO-PARENTS DISAGREE: The Neurotype Mapping Session

The Conflict: One co-parent sees ADHD ("She's just impulsive and distracted"). The other sees ODD ("She's deliberately defiant and disrespectful"). You're implementing different strategies in different homes, confusing the child.

The Solution: The Mapping Session

Each co-parent completes the Neurotype Navigator independently. Don't discuss or influence each other's observations. Base it only on what you've seen in your own home.

Compare your maps in a neutral setting (coffee shop, park—not at handoff or during conflict). Use a mediator if communication is difficult.

Find the overlap. Circle traits both parents checked. These are your "consensus traits" and should guide your shared strategies.

Discuss the differences without judgment. If Mom sees PDA traits and Dad doesn't, ask:

- "What does the child do at your house when you ask them to do something?"

- "How do you phrase requests?" (Commands vs. declarative language may explain different responses)

- "What's your tone like when you're stressed?" (Harsh tone may trigger ODD-like defiance in one home, not the other)

Create a shared "Priority Traits" list. Pick the top 3 traits both parents see, then pick 1-2 strategies for each that both homes can implement.

Agree on a trial period. Test the shared strategies for 3-4 weeks. Reconvene to assess: Did behaviors improve? Stay the same? Get worse?

Seek professional tiebreaker if needed. If you fundamentally disagree, bring both maps to your child's therapist, psychologist, or pediatrician. Ask: "Based on your clinical observations, which profile fits best?"

Example: Sarah sees ADHD + ODD. Mark (Dad) sees "just ODD" (thinks she's manipulative and choosing to be difficult).

Mapping session:

- Overlap: Both see emotional intensity, refusal to follow rules, forgets instructions

- Difference: Sarah sees hyperfocus and time blindness (ADHD); Mark doesn't notice these at his house

- Discovery: Mark's house has fewer high-interest activities (no Lego, no art supplies). Chloe doesn't hyperfocus there because there's nothing to hyperfocus on. Mark interprets her boredom as defiance.

- Agreement: Both will try ADHD strategies (visual schedules, movement breaks) + ODD strategies (calm tone, repair rituals) for 4 weeks. If ADHD strategies help, Mark will acknowledge the ADHD component.

Key Principle: You don't need identical neurotype interpretations. You just need compatible strategies that don't contradict each other. A visual schedule helps ADHD, Autism, AND ODD children—so start there.

---

Survival Tips: Summary Cards for the Voyage

Cut these out (mentally or physically) and tape them to your fridge or dashboard. These are your emergency flares when you are lost in the storm.

Survival Card 1: The ADHD "Brake Check"

- The Scenario: You are shouting instructions from the kitchen; the child is ignoring you.

- The Reality: They are not ignoring you; they are buffering. Their working memory is full or their attention is hyperfocused elsewhere.

- The Strategy: Eye-to-Eye, Knee-to-Knee. Do not shout from another room. Go to them. Touch their shoulder (if tolerated) to break the focus stream. Wait for eye contact. Give one instruction at a time. Ask them to repeat it back.

- Mantra: "Connection before Direction."

Survival Card 2: The PDA "Low Demand" Pivot

- The Scenario: You ask them to get dressed. They scream "NO!" and run away or go limp.

- The Reality: "No" is a panic response, not a behavior problem. The demand triggered a threat response.

- The Strategy: Drop the rope. Stop the power struggle immediately. Back off to lower their anxiety. Then, re-approach using Declarative Language. Instead of "Put on your coat," try "It’s raining outside today." Let them connect the dots. Offer autonomy: "Do you want the blue coat or the red coat?"

- Mantra: "You are safe. I am not controlling you. We are on the same team."

Survival Card 3: The ODD "Shield Lowering"

- The Scenario: You correct a small mistake. They explode, calling you names and refusing to apologize.

- The Reality: They are fighting a war you can't see. They feel shamed and unsafe.

- The Strategy: Sideways Parenting. Engage while doing something else (driving, walking, drawing). Direct eye contact can feel confrontational to an ODD child. Validate the feeling, even if the behavior is wrong: "I can see you are furious. I would be too if I felt unheard." Wait until they are calm to discuss the behavior.

- Mantra: "My calm is their co-regulation. I will not join their storm."

Survival Card 4: The Autism "Sensory Detective"

- The Scenario: A sudden meltdown in a public place (store, party).

- The Reality: Behavior is communication. A meltdown is often sensory pain or cognitive overload.

- The Strategy: Scan the environment. Is it too loud? Too bright? Are there too many smells? Stop talking (auditory input adds to load). Create a "sensory airlock" (sunglasses on, headphones on, move to a quiet corner/car). Apply deep pressure (squeezes) if it calms them.

- Mantra: "Reduce the input, increase the safety."

Conclusion: Every Child is a New Sea

As we close this chapter, remember: The chart is not the sea.35 The definitions and neuroscience here are just a guide. Your child is the sea—complex and alive.

One child may have ADHD traits that look like ODD because of forgetfulness. Another may have Autistic traits that look like PDA because of sensory overload. Real children do not always fit the DSM-5.

Your job is not to force your child to fit the chart. Your job is to sail these waters together. Return to the compass of curiosity. Ask "Why?" before you ask "What?"

In the co-captaincy charts of Chapter 3, we will discuss how you and your co-parent can navigate this world together. The voyage continues.

---

Chapter 2 Appendix: Science Spotlights & Field Guides

Science Spotlight: The "Amygdala Hijack"

Relevant for: Autism, PDA, ODD

Imagine the brain has a smoke detector called the Amygdala. Its job is to spot danger (fire!) and activate the body's alarm system (Fight/Flight/Freeze). In neurodivergent children, this smoke detector is often set to "Extra Sensitive." It goes off not just for fire, but for burnt toast, a loud noise, a change in plans, or a stern look.

When the alarm rings, the Amygdala cuts the connection to the Prefrontal Cortex (the "Thinking Brain"). The child literally loses access to logic, reason, and language. You cannot reason with a child in an Amygdala Hijack any more than you can teach math to someone who is on fire. You must put out the fire (soothe the nervous system) first. Only when the alarm is off can the Thinking Brain come back online.¹

Science Spotlight: "Monotropism" (The Autistic Focus)

Relevant for: Autism, AuDHD

Neurotypical brains are "polytropic"—they can split attention across many things (social cues, background noise, the task at hand) like a wide net. Autistic brains are often "monotropic"—they possess an attention tunnel that pulls them deeply into one thing at a time.²⁰ This is the source of their incredible focus ("special interests") and flow states.

However, it also explains why transitions are painful. Pulling a monotropic child out of their focus flow is physically jarring, like being yanked out of a deep sleep. It causes disorientation and distress. Respecting the "flow"—giving warnings, allowing time to close the tunnel—is key to reducing transition-based meltdowns.

Field Guide: Is it ODD or PDA? A Quick Difference Checklist

| Scenario | Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) | Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) |

|---|---|---|

| Reason for "No" | Often reacting to perceived injustice, authority, or anger. "You can't make me!" (Fight response). | Reacting to the demand itself causing anxiety/loss of control. "I literally can't do it." (Panic response). |

| Response to Rewards | Often responds to rewards if the relationship is good and the reward is valued. | Often resists rewards because the reward itself feels like a pressure/demand/manipulation. |

| Social Skills | May have typical social understanding but chooses to defy or argue. | May use sophisticated "social lubrication" (distraction, role-play) to avoid the demand before exploding. |

| Best Approach | Connection, fairness, picking battles, praise (carefully), "Sideways Parenting." | Low demand, collaboration, indirect/declarative language, masking the demand (strewing). |

Works cited

- Revolutionize Communication: Harnessing Neurodiversity-Affirming Language, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://moveupaba.com/blog/neurodiversity-affirming-language/

- Deficit, difference, or both? Autism and neurodiversity. - Developmental Psychology, accessed on December 21, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028353

- Hallowell, Edward M., and John J. Ratey. (2021). ADHD 2.0: New Science and Essential Strategies for Thriving with Distraction. Ballantine Books.

- Your Brain Is a Ferrari - ADDitude, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.additudemag.com/how-to-explain-adhd-to-a-child-and-build-confidence/

- Co-Parenting a Neurodivergent Child - Reese Law Office, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://reese.law/co-parenting-a-neurodivergent-child.html

- Unraveling ADHD: genes, co-occurring traits, and developmental dynamics, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.life-science-alliance.org/content/8/5/e202403029

- The known and unknown about attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) genetics: a special emphasis on Arab population - Frontiers, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2024.1405453/full

- Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. - Psychological Bulletin, accessed on December 21, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65

- Nine Key Takeaways: Co-Parenting Considerations for Families with Neurodivergent Children: What Family Law Professionals Need to Know - OurFamilyWizard, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.ourfamilywizard.com/blog/nine-key-takeaways-co-parenting-considerations-families-neurodivergent-children

- Considerations regarding child and parent neurodiversity in family court - Massachusetts Chapter AFCC, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://maafcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/FCR-Pickar-Considerations-Neurodiversity-2022.pdf

- Emotion dysregulation in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis - BMC Psychiatry, accessed on December 21, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2442-7

- ADHD and Co-occurring Conditions - CHADD, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://chadd.org/about-adhd/co-occuring-conditions/

- The heritability of clinically diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. - Karolinska Institutet - Figshare, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://openarchive.ki.se/articles/journal_contribution/The_heritability_of_clinically_diagnosed_attention_deficit_hyperactivity_disorder_across_the_lifespan_/27242163

- ADHD Causes: Is ADHD Genetic? - ADDA - Attention Deficit Disorder Association, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://add.org/is-adhd-genetic/

- Impact of Comorbid Oppositional Defiant Disorder on the Clinical and Neuropsychological Characteristics of Korean Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder - PMC - NIH, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10620339/

- AuDHD: Stories of Life with Autism and ADHD - ADDitude, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.additudemag.com/audhd-autism-adhd-experience/

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder | Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/oppositional-defiant-disorder

- When Parents Disagree About ADHD Medications - ADDitude, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.additudemag.com/when-parents-disagree-about-adhd-medications/

- Free Neurodiversity Printables!, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://therapistndc.org/education/free-neurodiversity-printables/

- Tooth Brushing and Sensory Overload: 15+ Tips for Neurodivergent Kids, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://neurodivergentinsights.com/sensory-friendly-toothbrushing-tips/

- Demand avoidance - National Autistic Society, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/behaviour/demand-avoidance

- Neurodivergent Affirming Language Guide - Neurodiverse Connection, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://ndconnection.co.uk/resources/p/nd-affirming-language-guide

- When you and your child's father disagree on a diagnosis - Hofheimer Family Law Firm, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://hoflaw.com/blog/when-you-and-your-childs-father-disagree-on-a-diagnosis/

- Pathological Demand Avoidance: Parent's Guide to Extreme Defiance - ADDitude, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.additudemag.com/pathological-demand-avoidance-strategies/

- PDA traits, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/what-is-pda/pda-traits/

- accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/what-helps-guides/helping-your-pda-child-with-dressing/#:~:text=Using%20different%20language%3A%20instead%20of,while%20they're%20doing%20it.

- Explaining (Reframing) Oppositional Behavior to Kids, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://explainingbrains.com/explaining-behavior/

- Oppositional Defiance or Faulty Neuroception? - Dr. Mona Delahooke, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://monadelahooke.com/oppositional-defiance-faulty-neuroception/

- Explaining Neurodiversity to Kids – A conversational Script for Parents Tool - ECHO Autism Communities, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://echoautism.org/autism-resource/explaining-neurodiversity-to-kids-a-conversational-script-for-parents-tool/

- When Autism and ADHD Occur Together - American Psychiatric Association, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/apa-blogs/when-autism-and-adhd-occur-together

- The comorbidity of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder - Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, accessed on December 21, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.2013.840417

- Extreme/'pathological' demand avoidance: an overview - Paediatrics and Child Health, accessed on December 21, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paed.2020.09.002

- Rewards and Consequences with PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance), accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.stephstwogirls.co.uk/2019/10/rewards-and-consequences-with-pda.html

- Teaching Excellence: The Definitive Guide to Nlp for Teaching and Learning - Index of /, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://www.ayanetwork.com/aya/research/Teaching%20Excellence%20The%20Definitive%20Guide%20to%20Nlp%20for%20Teaching%20and%20Learning%20(Richard%20Bandler%20Kate%20Benson)%20(z-lib.org).epub.pdf

- The trap of "I am not an extrovert" - Hacker News, accessed on December 20, 2025, https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=42514127